The last of my articles about the exploits of anti-fascist super mole Ray Hill. This time – how he engineered the collapse of British Movement, then the UK’s biggest openly neo-Nazi organisation.

When Britain’s National Socialist Movement leader Colin Jordan emerged from prison in 1968, he knew things would have to change. He’d served 18 months under the Race Relations Act for publishing a violently anti-Black leaflet entitled “The Coloured Invasion” and he really didn’t fancy any more jail time. So, while the attachment to Hitler would remain, utterances on race in future would be tailored to stay – just – the right side of the new law. And the NSM would be renamed British Movement.

When Jordan polled 3.5% in the Birmingham, Ladywood by election in 1969, it was taken as a vindication of the new strategy. Jordan’s election agent in Ladywood was a young Ray Hill, a prominent BM activist and highly regarded member of the organisation’s directorate. Shortly afterwards, Hill and his family emigrated to South Africa where he was to become Chairman of the South African National Front.

Disaster struck BM in 1975 when Jordan was convicted of stealing women’s knickers from Tesco in Coventry. He pleaded he had been “framed by the Jews” but he had little choice other than stand down as leader. His place would be taken, temporarily he thought, by his deputy, Michael McLaughlin, the Liverpudlian son of a communist who fought with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War.

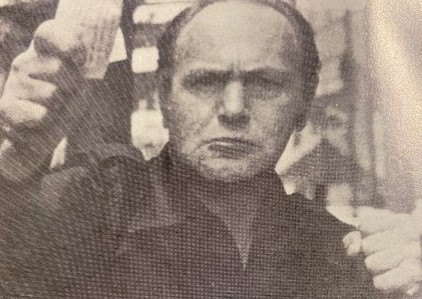

McLaughlin had joined British Movement soon after its launch in 1968 and was a staunch national socialist. But once he had control of the organisation, he made clear to Jordan that the former fuhrer’s days as leader were over. Sulking, Jordan retired to Yorkshire where he published an occasional newsletter fulminating against Jews, Blacks, the Reds – and Michael McLaughlin.

The new leader meanwhile targeted a younger male, working class demographic that would provide BM with a more combative, exciting appeal. By 1980 membership had increased from a few hundred to some 3,000, and the money was rolling in.

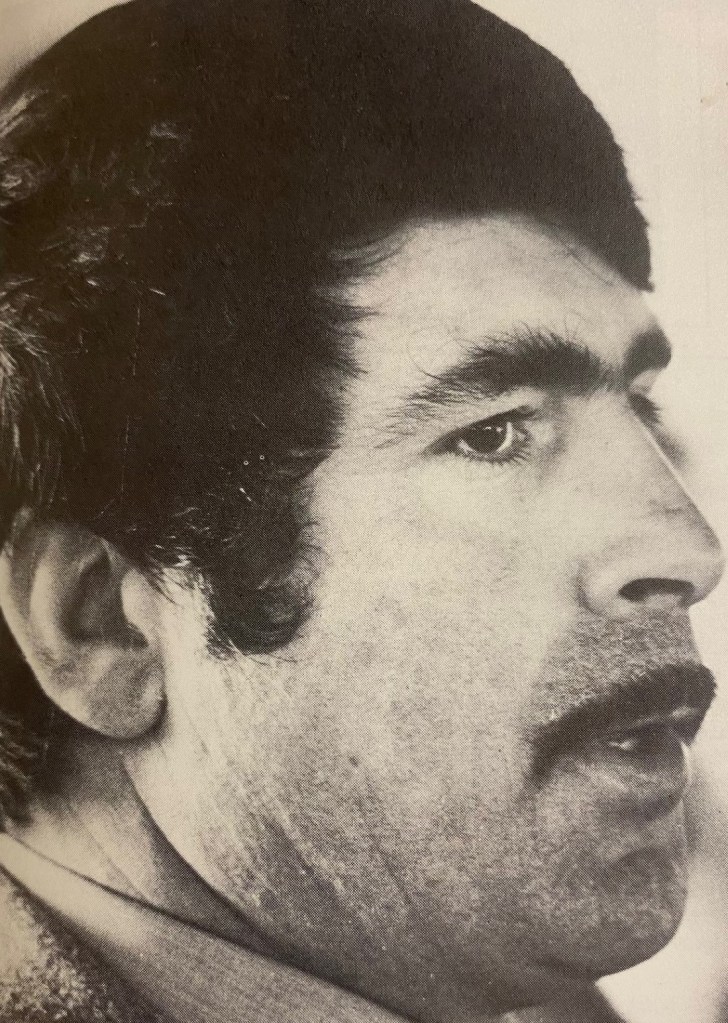

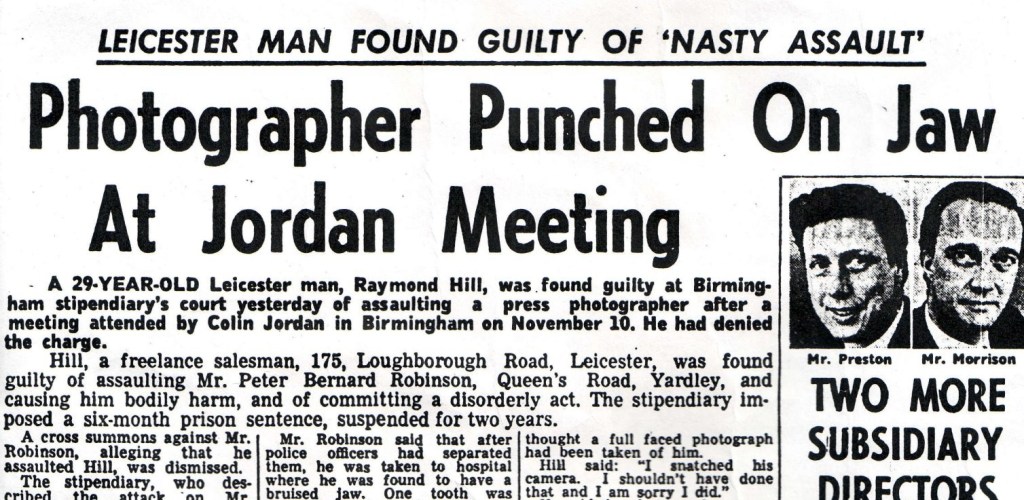

Ray, whose Damascene conversion away from nazism whilst in South Africa I have written about elsewhere offered his services to Searchlight in 1979, shortly after his return from South Africa, and his impeccable credentials on the British far right offered a highly attractive opportunity in relation to BM. Ray was, after all, the architect of BM’s famous election performance in Ladywood in 1969. He’d fought toe to toe with their opponents and even been convicted of assaulting a press photographer trying to take pictures of Jordan after a meeting in Birmingham. His reputation as a political bruiser and agitator would go down very well with BM’s growing young, aggressive skinhead membership.

This was the plan: Ray would join BM and use his reputation to build his own base of support amongst the membership. Then he would throw down the gauntlet to McLaughlin. Either Ray would win the struggle, take over British Movement and drive it into the ground or he would be expelled, split the organisation and take a large section of the members into the wilderness leaving only a rump behind. Either outcome would be a very desirable result.

When Ray wrote to McLaughlin in June 1980, McLaughlin didn’t hesitate. The two met at British Movement’s shabby two room headquarters above a mini cab office in North Wales and, by the time he left, Ray had been appointed Leicester BM Organiser and Area Leader.

The Leicester BM branch was moribund, but Ray had little trouble signing up some of the more hard-line former NF activists locally and soon had around two dozen members. A couple of quick-hit, high-profile local campaigns and the BM were garnering headlines in the local press. McLaughlin was purring. He wrote to Ray:

It’s gratifying to know that in Leicester we have someone who can be left to get on with the job and do it cleverly and with competence…in the immortal words of Adolf Hitler, in their greatest hour of need, the people will grasp the hand of national salvation.

Ray made his first play at a BM march in Welling, south London in October. McLaughlin was not planning to be there and asked Ray if he would stand in for him and make the keynote speech.

Would he?

Oh yes, he certainly would…

Ray headed the march making Nazi salutes then gave a barnstorming speech attacking not just the usual enemies but also the police for whom the 200 or so skinheads in attendance had little love. He was cheered to the skies. Then, speeches over, he lost no opportunity to work the crowd, quietly badmouthing McLaughlin:

“He’s sat at home in Wales while I’m here on the frontline with you lads. Don’t call that leadership myself…”

McLaughlin didn’t see what was coming. He wrote another glowing letter to Ray congratulating him effusively on his Welling performance. And Ray carried on sowing dissent.

The next time BM marched publicly, in Paddington, west London, the outcome was pretty much determined. McLaughlin spoke first, giving a speech that was characteristically turgid and pompous, receiving only polite applause. Then Ray spoke. Again, he tore into the police and again he was greeted with delirious clapping and cheering. But worse, some of the skinhead marchers then broke into a chant: “Ray Hill! Ray Hill!” to accompany the Nazi salutes they directed enthusiastically at Ray. McLaughlin watched from the side of the platform with a face like thunder. The penny had dropped…

He had a problem.

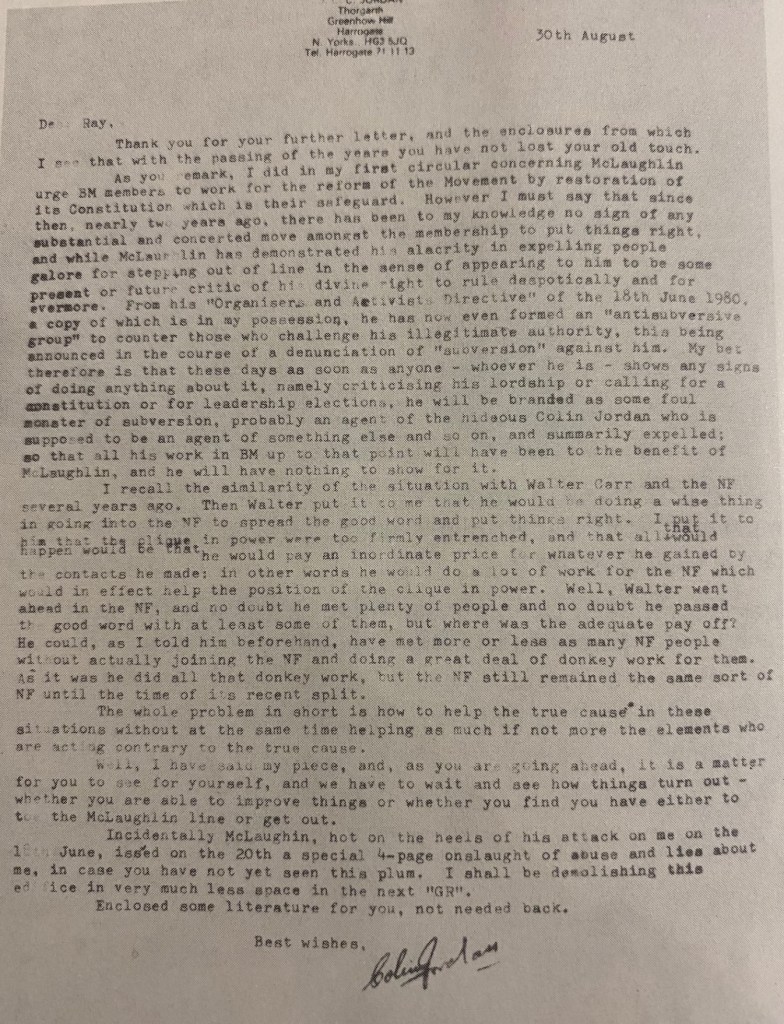

Ray’s next move was to seek advice from Colin Jordan. It would help his cause no end if he could claim that the old man was behind him. Jordan, still smarting from his own treatment by Mclaughlin, was happy to oblige. He suggested an escalating campaign for internal reform of the party to put pressure on McLaughlin. But, before this could begin in earnest, McLaughlin moved against Ray and expelled him from British Movement. It was earlier than we had expected, but no matter. The die was cast.

From BM branches all over the country came howls of outrage. Leicester branch declared that it regarded Ray as party leader. Leading activists around the country pledged their support. Ray distributed a “more in sorrow than in anger” statement amongst the membership, insisting that he had no designs on the leadership, and that his expulsion was not just wrong, but unlawful. He was a member in good standing and, if necessary, would fight his expulsion in the courts:

“I do not intend to foster or take part in any ‘split’ of the Movement. I do not aim for the leadership of the Movement. I do, however, insist upon justice and further insist that I am, and shall remain, a member of the BM who is entitled to all the rights and privileges of such membership…

“Whoever the leader may be, however, I, Ray Hill, will remain in the British Movement”.

McLaughlin threatened to expel any members who associated with Ray, but it was an empty threat. He would have precious few members left if he carried it out and he knew it. Most BM organisers and probably half the members were in Ray’s camp and public endorsements from Colin Jordan, veteran nazi Robert Relf and the League of St George meant it was game over.

The killer blow came when Ray launched a legal action against his expulsion. McLaughlin could not back down but nor could he afford for very long the expensive legal advice he was forced to take to mount a legal defence. Ray, on the other hand, was being legally advised, in the early stages at least, by Leicester-based BDP leader and solicitor Anthony Reed Herbert, free of charge.

The case dragged on but, in September 1983, Michael McLaughlin announced that British Movement was being shut down, complaining bitterly that he was being forced into it by the enormous legal bills incurred contesting Ray’s writ. And the matter had never even come to trial.

It would be another six months before Ray would appear on Channel 4, baring all, in The Other Face of Terror and McLaughlin, not to mention Colin Jordan, Robert Relf, Anthony Reed Herbert and all the others who gave Ray such sterling support and assistance, would realise the humiliation they had suffered at the hands of their hated enemies at Searchlight.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of Searchlight

Leave a comment